4433/17352

Going for a brain scan in an MRI machine is probably usually a cause for some concern, probably a sign that there’s something wrong in your head. But today I was asked to have a brain scan for rather more jolly (though still deeply scientific) reasons. The University College London wanted to scan my brain as I played a solo version of the “Just A Minute” game to try and find out the differences between the brains of professional speakers/improvisers and the normals. Maybe they were going to discover there was something wrong in my head, but just in the way it is wired. Though it did have the added benefit that if there was something actually physically wrong in my brain, then we’d find that out as well.

It was nice to be helping out science by talking a load of shit inside a giant magnetic scanning machine, but it was exciting to do this for personal reasons. I would find out what my brain looked like, how it worked and I was secretly hoping they would discover that my grey matter was special in some way or had some additional little bend or section which enabled me to be so very funny. I don’t want to say that I am the next step in human evolution, that is for science to decide.

I was taken into a basement at the University, by a young man I didn’t know and who could just have pretended to be interested in studying my brain and have different plans for me. And even if he was bona fide from what I know about psychological experiments they usually tell you they’re testing one thing, when they’re really testing something else, like your willingness to electrocute someone or the endurance of human patience. Or we might be about to do my own version of Total Recall. I was very much looking forward to the bit where I’d say, “You think this is the real Richard Herring. Ha ha ha...… it is!” (and just hope that the guards with the guns would be more concerned with looking stupid and shooting the wrong thing than not want to take a chance and just shoot everything - I mean is it worse to be tricked by a hologram or be shot. Those guards in Total Recall were idiots).

Even by the standards of my largely dull, then occasionally odd life, this was a strange experience. So they could study my brain properly it was important that I kept my head still while all this was happening and because the machine is a bit noisy I had ear plugs in, so my head was surrounded by cushioning and placed inside a helmet with a microphone in it. I was lying on my back and then conveyed backwards into the tubular machine. It wasn’t one for the claustrophobes and I was worried that my natural fidgetiness might screw everything up (also I am quite an animated talker so wasn’t sure I’d be able to keep still enough anyway). I was going to be in there for about half an hour, but I had a little ball I could squeeze that would sound an alarm if I got freaked out. The worst thing about it for me was getting little annoying itches that demanded to be scratched, but which I had to leave be. It was all psychological. And again that might have been the test. I also thought that the secret test might be to see how long I would carry on with the task before giving up. I decided to be like Abed in Community and to stay in there until I had broken the people doing the experiment.

I had to do 30 second bursts of talking about a subject that was presented to me on a screen (I was meant to try to avoid repetition, hesitation and deviation, but would not be buzzed or penalised for mistakes - if i had been them I would definitely have included an electric shock for errors element to the test, otherwise, what’s the point?). In between to act as a control and to see how my brain functioned in a circumstance where I didn’t need to improvise I had to count upwards from a displayed number for 30 seconds. I actually found this a lot harder than talking about the subjects. A couple of times I got to 79 and very nearly jumped to 90. It’s been a long time since I have counted upwards for no reason and it’s easy to forget some of the numbers. Was this the real test? To see if a middle-aged man could still count. The Just a Minute thing was a brilliant distraction. The stress engendered in trying to work out which number came next might skew the results - “This subject seemed to find it more difficult to count to 90 than to talk about Scotland…” I might get a syndrome named after me.

The testers did say that the control group of non-professional speakers found the idea of talking on a surprise subject very difficult. On being presented with France they would say, “I dunno. I’ve never been there.” I bet they didn’t nearly forget about the existence of numbers in the 80s (twice) So it’s amazing what things can seem simple to one people are so difficult to another.

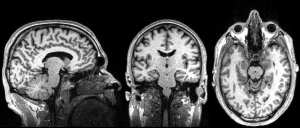

Afterwards they showed me cross section of my brain. It has some holes in it, but apparently they’re meant to be there. I had kept still so you could see the little spreading tendrils and the crinkly stuff at the edges. In old people (and some young people too) you can start to see wear and tear around the edges (actually I don’t think it ever tears), but they said my brain looked like a young brain (which doesn’t explain why I keep forgetting the names of people I know really well). I asked if there was anything unexpected or exceptional there but they didn’t seem keen to reveal if that was the case. Most of the results will take a while to process. But it was amazing to see my brain, as well as a hairless representation of my head and face, which looked on screen like it was carved from wood.

Back in the very early days of this blog

I mourned the fact that I would never see my own skull, but today I did see (an admittedly computerised version) my own brain. And I suppose with modern technology it would actually be very possible now to scan a person’s skull and then do a 3D print out of their skull, so what I thought was impossible is sort of now possible, less than 12 years on. It wouldn’t actually BE my skull. But it would let me know exactly what my skull looked like. And I could hold it.

I asked them to show me my favourite bit of the brain, the hippocampus which deals with short term memory.

This guy had his removed to treat his epilepsy with terrible, but fascinating results. Mine was still there, as I suppose this blog proves.

It was a treat to get to look inside my own head and apparently they will be sending me the scans so I can play with them myself on my computer. And the results will take a few weeks to process, at which point I will discover what the team were really testing. Thanks to Joseph and the rest of the team for having me along.

The video RHLSTP with Sue Perkins is now up in the usual places

itunes

Audio up soon.